There are two tribes within Christianity who are holding a debate about which is the better way to faith, that of simple trusting faith or that of the struggle of doubt. In a sense, this is talking to this debate but is doing so by picking up an aspect that is overlooked. My faith, which is the one God blessed me with falls into neither camp and can appear to fall in both. My faith is both searching and inquiring without going into doubt.

The first thing I want to say, is there is not one sort of faith that is right and another that is wrong. The form your faith takes is part of your spirituality, it is the shape God has given you and thus part of your call. Whether your faith is a contented trust with no desire to explore further, the desire to spend time in quiet contemplation of the divine, the avid study of the Bible, the desire to seek a world that conforms to God’s justice, a servant spirit that is drives you to serve others, the doubter who wrestles with God, a combination of all or some of these or another form entirely, it is both uniquely yours and also one of the myriad forms that God has made. Do not feel that it is wrong because it is not the same others. All in the end bring us to the same place, the compassionate heart of God.

The second thing to say is this is personal. I am talking of one of the strong strands within my own faith calling. It is not the only strand; I can trace at least two others: a contemplative strand and an activist strand. Indeed the contemplative strand is going to lurk in the background as I write this. These two intertwine in complex patterns within my vocation, the contemplative is surprisingly strong but the scholarly is more developed. So I am going to need to be aware of how this piece is shaped by my experience.

I am re-reading Dangerous Wonder by Michael Yaconelli as I thought it might help a friend and then found it was no longer on my bookshelf. I have just finished the chapter on Risky Curiosity which is making me think. My PhD business cards to say “Basically I have been compelled by curiosity” which is a quote by Mary Leakey but sums up my approach to research pretty succinctly sums up my approach to research. It is driven by trying to answer questions that intrigue me. I am not particularly limited by subject or discipline. I find that working with passionate people who are researchers invigorating. This naturally spills over into my faith. So much so that my doctorate is in theology, albeit contextual theology rather than systematic with a focus around ecclesiology and how we do Church. The chapter naturally appeals to me and is confirmatory rather than challenging as other chapters in the book. However, it did not arrive in my reading alone.

Last Thursday I ended up talking with a friend about our pictures of the divine. Neither of us really has much time for the picture of God as the old man up in the sky who is a loving Grandpa, a sagacious arbiter of our fates and ultimately sovereign. We tend to struggle with words such as light, fire, flames, communion, dance, aurora, plasma, vortex, compassionate, beloved, transcendent, imminent, intimate, personal, furnace. We know we are struggling to put into words our vision. I know many people say God is as in Jesus and that is good as far as it goes. Let me take you to a detail of Michelangelo’s painting of Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel

Now if you look carefully the hands are apart. Talking pictorially I would say Christ is the light that emanated from the point at which God’s hand touched Adam. Christ is both the Beloved of God and the Lover of Adam. It is God who reaches out to humanity not humanity that manages to reach God. Let me leave this image here except to point out that even when I am thinking of Jesus I at times am thinking in terms of light and to point out Jesus is reported as saying “I am the light of the World” (John 8:12).

So when on Friday (28th August 20) was St Augustine’s day and the Office of readings contained the passage

Having convinced myself that I had to return to myself, I penetrated my interior being, with You as my guide. And this I was able to do because You, Lord, succoured me. I entered and I saw, with the eyes of my soul, in one way or another, above the capacity of these same eyes, above my mind, the immutable light; not the ordinary and visible light seen by any man, no matter how intense or clear it might be, being nevertheless incapable of filling all with its magnitude. Rather, it was a completely different light. It was not merely above my mind, like oil over water or like the heavens above the earth. Rather, it was light in the Most High, since this Light made me, and I was at the lowest, as I was made by It. This Light is known by the one that knows the truth.

St Augustine Confessions

Now it came as a bit of a surprise to me but then my brain almost at once started to recall the papers found in the coat of Blaise Pascall

The year of grace 1654,

Monday, 23 November,

the feast of St. Clement, pope and martyr, and others in the martyrology.

Vigil of St. Chrysogonus, martyr, and others.

From about half-past ten at night until about half past midnight,FIRE.

Blaise Pascall – Memorial

GOD of Abraham, GOD of Isaac, GOD of Jacob

not of the philosophers and of the learned.

Certitude. Certitude. Feeling. Joy. Peace.

GOD of Jesus Christ.My God and your God.

Your GOD will be my God.

Forgetfulness of the world and of everything, except GOD.

He is only found by the ways taught in the Gospel.

Grandeur of the human soul.

Righteous Father, the world has not known you, but I have known you.

Joy, joy, joy, tears of joy.

I have departed from him:

They have forsaken me, the fount of living water.

My God, will you leave me?

Let me not be separated from him forever.

This is eternal life, that they know you, the one true God, and the one that you sent, Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ.

I left him; I fled him, renounced, crucified.

Let me never be separated from him.

He is only kept securely by the ways taught in the Gospel:

Renunciation, total and sweet.

Complete submission to Jesus Christ and to my director.

Eternally in joy for a day’s exercise on the earth.

May I not forget your words. Amen.

You will see a surprising similarity between the way two great thinkers describe a spiritual experience. I do not think that they are in any way equivalent. Augustine was a 4th Century Christian Bishop in North Africa. He spent quite a bit of time arguing with Manicheas while Pascal was a 16th Century French philosopher was a Jansenist which could be seen as a Catholic form of Calvinism. Though Pascal, no doubt, knew Augustines work as it was required reading for theologians, I doubt they would have been intellectually in agreement with each other. What they do have is strong enquiring minds.

I have heard a rumour of a third great thinker who had such an experience. The story as I recall it is that towards the end of his life Thomas Aquinas had such a spiritual experience while participating in the Eucharist that he felt that all the rest of his life was wasted. Lets for the moment assume it as plausible. Then we have three great intellects all of whom have an experience of the divine that to them overshadows completely their intellectual endeavours. They know that even at the height of their intellectual work they fail to communicate the essence of the divine and fall into silence or poetry. To put it in a way that is indebted to C.S. Lewis, their experience is similar to children playing at being lion hunters when a real lion turns up. I must admit if these are only children then they are some of the most skilful lion-hunters among us intellectually. Their experience does not nullify the immense value of their work one iota. It still stands as a statement to the rest of us about the nature of the divine. However to them, all abstract thought, even by our standard sublime abstract thought, was dirty dishwater when compared with the eternal spring of living water that is the experience of the divine.

I suspect there are others, in some traditions you do not write this down sort of thing, the mystical experience of the divine is not usually open to the sorts of requirements that the tradition demands. It is notable that Pascal did not publish his and as I said earlier I have not managed to check the story I remember about St Thomas Aquinas. Maybe Eastern Orthodoxy would be more receptive but the Western tradition with its strong rational bias finds these experience often though personally powerful, not valid evidence within the debate. Augustine, Aquinas and Pascal are able to acknowledge them because they are such good rational thinkers. A lesser thinker, which is most of us, will shire away because it would undermine our status as rational thinkers.

Let me change tack for a while and look at the story of Job. I am not looking at Job’s friend, nor making a stab at the theology of suffering that the author proposes. I am wanting to look at Job’s interaction with the Divine. The story is well known. Job, a righteous man, is devastated by Satan acting with God’s permission. His three friends come to comfort him but after a week of silence finish up debating theodicy instead. To his friends only some evil done by Job could justify this action by God towards him However, they are defeated in justifying God’s action to Job who insists on his own righteousness and that he wants to hold God to account. A young man, Elihu, feels the friends have given up too easily and doubles down on Job. Then in chapter thirty-eight God appears in a tempest and starts cross-questioning Job. Job gives in so quickly it is embarrassing; with God present, he pleads ignorance. Faced with the presence of the Almighty Job basically opts for silence. There is always that niggle, that if it had been us rather than Job we would probably have asked more. Eventually, God speaks to the friends instead of Job and where he has been giving an extended account of his actions before God is now succinct and imperious:

After the Lord had spoken these words to Job, the Lord said to Eliphaz the Temanite: “My anger burns against you and against your two friends, for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has. Now, therefore, take seven bulls and seven rams and go to my servant Job and offer up a burnt offering for yourselves. And my servant Job shall pray for you, for I will accept his prayer not to deal with you according to your folly. For you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has.”

Job 42:8-7 ESV

What is striking is that last sentence “For you have not spoken of me (God) what is right, as my servant Job has”. Job who has insisted on his righteousness and wanted to call God to account is held by God as speaking righteously whereas the pious words of his friends and Elihu are not right with their seeking to find fault with Job.

Now I am not claiming Job is a scholar, his questioning is driven not by curiousity but by his own suffering. He does, however, have two characteristics that I think mark many scholars: persistence and integrity. His persistence shows in his refusal to accept the friends plausible explanation and his integrity in that he does not allow him self to be classed anything other than righteous regardless of what is convenient for the theodicy of the times.

Now the book of Job is often likened to a play. I am not here to debate it but what we see is someone driven by the need to answer a question to the point where their questing is answered by the Divine. There is a problem if is a play; how do you show the awesome reality of God? That is what I suspect all the chapters of God’s speech is trying to do. It fails to the modern mind. The question is not solved, but Job falls silent before a reality that surpasses the question. This then links back to the earlier experience of Augustine, Pascal and Aquinas. The end of Christian scholarship is not to make God intelligible to humanity but to find oneself caught up in the joyous theophany of the Divine and to know oneself known by that which cannot be known. Those with this vocation seek to know and instead find ourselves known. In other words, the quest inevitably ends in failures but in so doing the scholar is found.

It is worth drawing some codicils and corollaries from this.

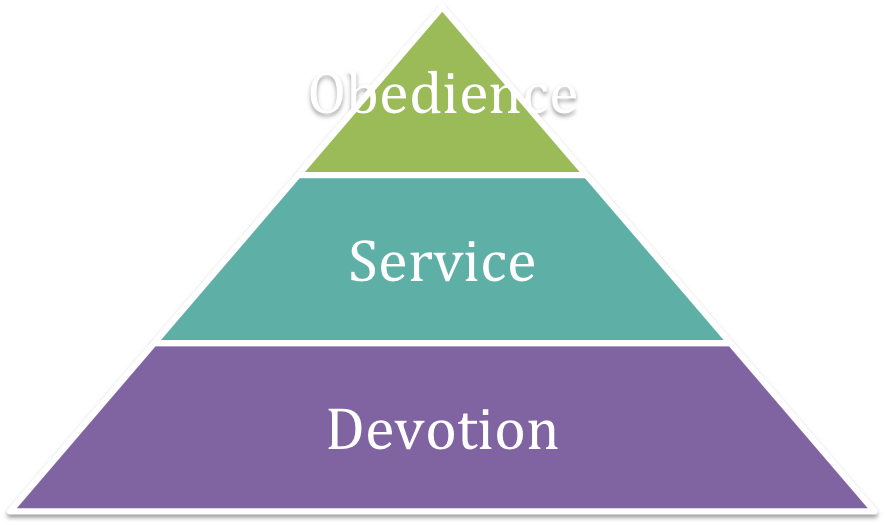

First importantly this is not the way to salvation, there is no way to that except through the cross. However, the lived-out nature of the way of the cross is different for different people. Normally it has three steps: obedience, service and devotion. Of these, I would see obedience as the highest. It is in Evangelical speak what is to accept Jesus as Lord and Saviour. The latter two just capture what it is to Love your neighbour and to love God. It is in our ability to Love our neighbour that the process of sanctification is most clearly seen. However, without the devotion or the desire to love God and seeking ways to express it, our obedience becomes rule-keeping and our service duty.

The form in which I am talking about scholarly vocation is that of devotion. The thing that drives this is our desire for God. I acknowledge that many with this vocation will find that amongst the service part of the vocation is the call to apologetics and to teaching the faithful. I would suggest that those are never the whole of their call in that area. The simple service of their fellows through acts of benevolence is never removed from a Christian. We can never serve Christ truly if we do not serve Christ in the people we encounter.

Equally the revelation here granted is not superior to that granted to those whose devotion is expressed through:

- service of others

- faithfulness in public worship

- evangelical zeal

- devotional practices

- contemplation

- service of the church

- or other acts driven by the desire for God

However, it should also be clear, that sometimes it is not the right thing to do to seek to stop someone from exploring their faith further. While it can and often does lead to an individual going through a time where their faith feels broken down, the risk of not allowing them to explore this way is for their faith to become sterile as they lose the devotion that powers their faith. The way through the desert is in the scholarly vocation as much as it is in any other but when water is on the other side of the desert then there is no merit in turning back to the stagnant springs you have left behind.

There is a risk as with all styles of devotion that we will mistake the means for the end and fall into idolatry. For a contemplative, that might be the calm the practice brings, for service to the church that might be the Church itself, for those who seek to bring about the kingdom that might be the changes in the way the world is structured. I can go on. For the scholar, it is the knowledge itself that becomes the idol. When the niceness of your theory becomes more important than speaking the truth of the nature of God, then your theory has replaced God. This is regardless of the academic plaudits you can earn for the attractiveness of your theory. In no other vocation does a commitment to speak honestly about the nature of God matter

I hope that in this piece I have argued that the scholarly vocation is a way of devotion to God that it seeks, in the end, God’s self-revelation and when that is granted the experience is on a par with other vocations of desire but a scholar finds themselves known rather than knowing. Arising from this that to seek to stop someone seeking this way is to put their faith at risk but that the big risk is not having their faith destroyed by the new knowledge but instead making the new knowledge an idol in place of God. There are similar idols for all vocational practices but to have no devotional element to your vocational practice is to find that your faith is running dry.